The Human Crusher in Syria

Sami DAOUD

The French historian Volney visited Syria and Egypt between 1783 and 1785, documenting his observations in his book Voyage en Égypte et en Syrie. At that time, Syria lacked a defined political structure or distinct cultural identity. The populations residing in this geographical area were identified based on their ethnic or sectarian characteristics, such as Kurds, Muslims, Christians, Yazidis, Druze, Alawites, and Ismailis. The Ottoman occupation frequently changed the names of administrative divisions and the borders of each province. Volney wrote that Syrians treated one another as enemies, distinguishing themselves through opposing classifications that perpetuated a state of constant war. Volney used the geographical term “Syria” to refer to a spatial expanse without defined borders, inhabited by divided peoples whose identities shared nothing in common except a rejection of what lay beyond them.

Religion functioned as a mechanism of governance, serving as the political ethos of local communities and an emotional dynamic exploitable for military purposes by those in power. Both the Ottomans and Safavids leveraged this by transforming sectarian entities into social divisions and politically sectarianizing them. Sectarian violence had already been embedded within Islamic religious sentiments through three continuous centuries of bloody wars, succinctly chronicled by George Tarabishi, Philip Hitti, and others.

The investment in religious fervor evolved after World War I. Japan built the Tokyo Mosque in 1937, attempting to compete with Germany in manipulating religious emotions. Germany had been the most prominent European presence in the Islamic world through its Orientalist missions. One of these missions was led by a German foreign ministry official named Max Oppenheim, who presented himself as an expert on the Arab Bedouins. He studied their martial traits and daily customs in a monumental collaborative work with other German Orientalists. Gradually, Islam’s image as a “fierce warlike religion” began to attract the attention of Hitler and Mussolini, both of whom maintained good relations with the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini, as noted in al-Husseini’s memoirs. Hitler was particularly aware of Atatürk’s methods of exploiting Islam to manipulate aggressive sentiments. These nations began incorporating religious fervor into the military activities of warring empires, leading to the reemergence of terms like “Crusader enemies” in political discourse—used by the Japanese against the British in India and China and by the Turks and Germans in Syria, Egypt, and Palestine.

The Roman term "Syria" first appeared in the third century BCE, based on an imprecise assumption by Herodotus. This designation disappeared from official records starting in the seventh century CE and remained absent until the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when the Ottoman Salnameh (administrative yearbook) of 1868 revived the term to refer to the province of Syria. At that time, it encompassed only Damascus and the Hauran region, while the province of Aleppo remained independent until 1925.

VOLNEY traveled across Syria much like Mark Sykes would later do, riding animals to move between small rural towns. At the time, there were neither transportation systems nor education in Syria, and the ancient Roman roads had been devastated by wars. Road construction was delayed until 1883 and remained limited in scope, despite some rapid developmental efforts initiated by Ibrahim Pasha during his rule over Syria from 1831 to 1840. Given the widespread illiteracy and lack of transportation, it was natural for the Syrian peoples to remain unfamiliar with one another. As a result, there is not a single document indicating the existence of a shared Syrian political project.

The transition of power following the end of Ottoman rule in 1918 occurred through a shift from Ottoman governors to what Albert Hourani described as the "notables class." From 1920 to 1949, power was concentrated in the hands of 52 families from the urban bourgeoisie, who were effectively the continuation of Ottoman bureaucrats and merchants. Therefore, the shift in power did not truly occur in 1920, when the British dispatched Faisal, son of Sharif Hussein, from the Hejaz to Damascus, where he ruled for only two years. Instead, the transformation began gradually with changes in agricultural policies and the emergence of chauvinistic ideologies among educated Syrian elites. These elites, influenced by Turkish nationalist zealots and German Nazis, adopted the Prussian concept of the "militant nation."

Other factors also played a role, such as relocating the military academy from Damascus to Homs, initiating the ruralization of the army, and transforming it into an ideological force under Akram al-Hourani. Additionally, economic changes occurred, including shifts in colonial economies at the expense of colonial powers and the development of trade and the exportation of Syrian agricultural products.

After four centuries of Ottoman occupation, described by Ernest Renan as the era in which reason was "killed," and supported by Arnold Toynbee and Viscount Percy in their co-authored book The Murderous Tyranny of the Turks (1917), Syria entered a period of decline. Muhammad Kurd Ali, in his memoirs, also noted that the Ottomans neither established schools nor paved roads -schools began to be built as privileges for governors starting in 1884-. For the Ottomans, as illustrated in the memoirs of Al-Budayri al-Hallaq (1701–1762), Syria was merely a source of conscription, taxation, and supplies.

Following the Ottoman era of decline, Syria transitioned to the French Mandate, which conducted numerous population censuses -all fortunately available in the French Diplomatic Archives-. The mandate introduced modern institutional structures in highly illiterate and fragmented societies, turning Syrian provinces into ethnically and sectarian divided states with dual administrations: a high commissioner and a local governor.

From the mandate, Syria moved into an era of military rule that has persisted uninterrupted to this day. Notably, Syrian Kurds were key figures in the military coups, starting with Husni al-Za’im in 1949, and including Adib al-Shishakli, Fawzi Selo, and others.

The French attempted to establish a Bedouin state in the Syrian desert, spending millions of francs on bribes to tribal leaders, but the effort failed spectacularly. Cultural and societal structures were incompatible with the concept of institutionalization, a condition that persists to this day. Syrian society continues to favor tribal and sectarian patronage over political elevation to the idea of citizenship. I mention the example of the Bedouin state in Syria because the country's population in 1921 was 1.2 million, increasing to 1.5 million by 1929, including 400,000 Bedouins. Illiteracy was deeply entrenched, resisting any attempts at civic institutionalization, and nationalist slogans served to obscure these realities, much as they do today.

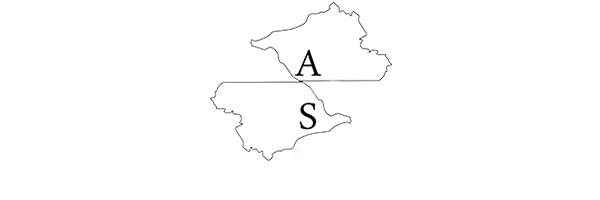

Syria is a geographical term for a modern and artificial political entity, dating back to 1939. Its initial borders were drawn with a pencil by Mark Sykes on a paper map on December 15, 1915, during a meeting at 10 Downing Street in London with the British Prime Minister. These borders remained fluid, subject to a series of agreements between France (the new occupier) and Turkey (the previous occupier) from 1921 to 1939. With France under German occupation and Charles de Gaulle delivering speeches from London to Free France and its colonies, the formation of Syria’s borders with Iraq and Turkey was dictated by the military alliances of post-World War I empires. This included French efforts to win over the Turks and encourage them to sever their historical ties with the Nazis.

Thus, despite the provisions of the 1936 Franco-Syrian Treaty and the League of Nations census in Alexandretta in 1937, France ceded the region to Turkey. Additionally, France and Britain relinquished the western part of the Kurdish region, formally incorporating it into Syria. The French Diplomatic Archives provide documents revealing the transformation of French policy in the Kurdish region and the process of its annexation to Syria.

The Kurdish politician Nuraddin Zaza noted in his memoirs that in 1940, Damascus had a football team named “Kurdistan,” which won the championship in Sham. Reviewing the arguments of Zaza’s three lawyers: an Arab from Aleppo, an Arab from Damascus, and a Kurd reveals the moral solidarity between Arabs and Kurds up until 1962. During my research on the history of hatred in Syria, I found no documents predating 1936 that indicated hostility between Arabs and Kurds. On the contrary, Arab publications from Beirut, Cairo, Baghdad, and Damascus supported the Kurdish struggle for establishing Kurdistan on its land.

It is worth noting that the first person to call for the establishment of Syria as an Arab state was the Kurdish thinker Abdul Rahman al-Kawakibi, according to Nicholas Van Dam, citing Albert Hourani. The first to abolish ethnic quotas in the Syrian parliament and army was the Kurdish president Adib al-Shishakli. The first Arabic language academy was founded by Muhammad Kurd Ali, the Arabized Kurd.

However, the ideas of Arab nationalist Ottoman citizen Sati' al-Husri, followed by Michel Aflaq, Zaki al-Arsuzi, and Akram al-Hourani, adopted Nazi principles, particularly those conveyed through Johann Gottlieb Fichte’s Addresses to the German Nation, translated by Sami al-Jundi. Passages from this work appear almost verbatim in Zaki al-Arsuzi’s The Ideal Republic (1965). Contrary to Hazem Saghieh’s interpretation of Arsuzi’s thought and his mistaken belief that Arsuzi drew his ideological model from the Jahiliyyah (pre-Islamic era), both Aflaq and Arsuzi Arabized Islam and Islamized Arab nationalism.

As a result, nationalist ideology became sacrosanct, and in this framework, there were no longer mere opponents in Syria—every opponent became an enemy. As Akram al-Hourani wrote in his party’s manifesto, Al-Shabab (1937), “Anyone who does not Arabize will be considered a foreigner to his nation,” a clause later adopted by the Baath Party’s constitution in 1947.

The cultural and emotional equation in Syria shifted dramatically after the Baathists seized power in 1963. Since then, no culture opposing the Baathist chauvinistic model has emerged. Instead, slogans glorifying perpetrators as symbols have proliferated, as seen in the blending of images of Saddam Hussein and Erdoğan with the flags of Syrian armed groups. According to the UN Commission of Inquiry report published on September 15, 2020, these groups committed crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing against Kurds in Kurdish cities that remain occupied by Turkey to this day. Since November 10, these Turkey-aligned Syrian political and military organizations have been orchestrating systematic incitement and hate campaigns against Kurds in Syria. Both secular extremists and Salafists have participated in these campaigns, culminating in acts like the targeted killing of Kurdish civilians in Manbij, as documented by the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

At no point in Syria’s ancient or modern history have the populations living within its borders coalesced into a single nation. The term “Syrian people” does not denote any political or cultural unity but rather serves as a geographic metaphor for communities’ incapable of interacting culturally or morally to form a cohesive nation. Since 2012, the country has been engulfed in a brutal civil war, forced displacements, and regional occupations rooted in Sunni-Shia sectarian loyalties. Ignorance is rampant across all social classes, compounded by a legacy of repression epitomized by Sednaya Prison, spanning over half a century. This is further exacerbated by a tribal political culture and a political and cultural system that has remained unchanged for decades. There is a tendency to reduce the previous regime to a handful of individuals and families, replacing the dominant sectarian and regional loyalties of one group with those of another. Essentially, the name of the dominant group changes, but the repressive tendencies remain entrenched within the same political framework.

This human grinding mill produces nothing but more hatred. What complicates matters further is that hatred, as a vile and malevolent act, finds acceptance among certain groups in Syria who embrace it as something desirable. Today, hatred has become a dangerous weapon in the hands of Turkey, which manipulates its Syrian proxies and directs them in a declared war of extermination against the Kurds in Syria.

Syria will not emerge from the abyss of hatred rooted in grudges too entrenched for reason or discourse to untangle. There is an infatuation with evil that looms over Syria, manifesting in mutual killings, dragging bodies through the streets, and mutilating corpses, all set to the rhythm of extremist slogans. It must be acknowledged that this country is broken, and one must recognize the depth of ignorance and malice that will inevitably hinder any suspended political projects. All indicators point to an eternal return to sacred violence.